Are you thinking of applying for the Homelessness Reduction Innovation Fund (HRIF)?

We have some great news. The third round of expressions of interest are now open, and we’ve developed this quick resource to help you build a strong application.

But first, a quick refresher about HRIF.

HRIF provides one-time grants to eligible communities for targeted, data-informed initiatives lasting up to 12 months that will measurably reduce homelessness.

It’s a $45-million fund, flowing out of the federal government’s $1 billion commitment to Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy, as announced in Budget 2024. It’s being administered by the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness (CAEH), in partnership with the National Indigenous Homelessness Council (NIHC).

The money will be disbursed throughout five rounds of funding over three years. Nearly $7 million has already been distributed to 16 communities in the first round of funding, with more reduction projects planned to start in early 2026 as part of round two.

These communities already have the foundational blocks of a strong homelessness response system:

| Quality, real-time By-Name Data of all people actively experiencing homelessness; and | Coordinated access, with all relevant agencies in a community coming together regularly to prioritize and find housing and support services for people on the By-Name Data. |

Crucially, each project introduced a key change targeting a specific improvement in their homelessness response system, and they followed the approach that we lay out in this article.

If these steps feel like a challenge, or you don’t know where to start, that’s okay. Our Improvement Advisors will be with you every step of the way!

The secret ingredient: Improvement science

There’s a quote we use often at CAEH, from quality improvement thinker W. Edwards Deming.

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets,” he said.

Homelessness is a result of systemic issues in a community’s housing system, so reduction projects are about making small changes and then taking lessons learned from the changes to improve local systems of care.

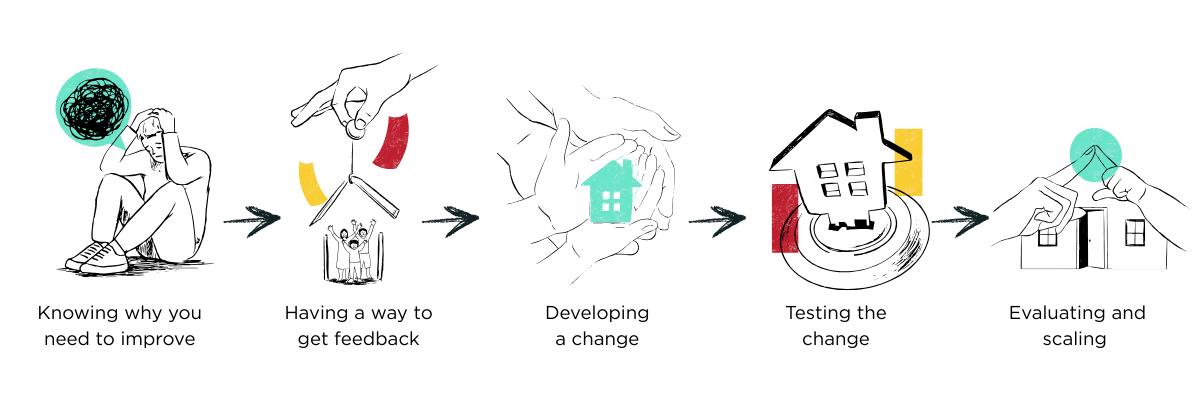

The model for improvement that we use, adapted from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, has five fundamental principles:

1. Knowing why you need to improve

A clear project goal (discussed further below) that is really intentional about what the change is that you want to see in your homelessness response system that will reduce the number of people experiencing homelessness, either by reducing the number of people falling into homelessness, or increasing or accelerating the number of people moving into housing.

2. Having a way to get feedback

There must be a source of data that is able to track in real time the direct outcome of the change being implemented. It means having an answer to the question: how am I going to use my local data to understand if the changes that I’m making are leading to improvement? This is where Quality By-Name Data comes into play. Communities use their aggregate inflow and outflow data to identify project ideas and then track progress toward their reduction aims or goals.

3. Developing a change

This step is like a science experiment, developing a hypothesis where you can make a reasonable prediction that one thing you do differently will have a specific impact. This change must be connected to the project objective and could range from a small action like altering a diversion form to adding a dedicated new staff resource to change the way you interact with clients. It does not need to be groundbreaking, but it must be new for the local homelessness response system in your community.

4. Testing the change

Before moving forward with a large, new, expensive change to the system, it’s important to minimize risk by testing or piloting the change. You don’t know if the new change is going to lead to a reduction in homelessness, so testing before scaling is essential. It also creates opportunity to regularly review the impact of the change, and adjust the project over time based on real-time learnings. There are a few types of measures that can help you test to see the impact (discussed below).

5. Evaluating and scaling

Once you’ve had the time to test the change, then it’s time to review the testing results, discuss the impact of the change to the system, if there are opportunities to improve the outcomes of the change, and finally to scale your innovation within the local context.

Interested in learning more?

Calls for Expressions of Interest now open! Learn more information and submit your Expression of Interest by 4 PM ET on March 13, 2026.

A strong aim targeting systemic issues in homelessness response

All communities eligible for HRIF will have real-time, Quality By-Name Data of the people actively experiencing homelessness—including information about when people first enter homelessness, how long they are unhoused, and when they are connected with a home.

This systems-level data can help you develop your problem statement, which will identify the nature and scope of the problem that you’re trying to solve. Maybe it is that you have high numbers of people falling into homelessness, or very low numbers of people exiting homelessness and into housing.

But that should be just the starting point. To develop a strong aim, you need to dig deeper into the root causes.

Think of this analogy. If you have a headache and take some pain relief medication, he symptoms will go away, but it doesn’t change the fact you are getting headaches because of insufficient sleep.

Think of this analogy. If you have a headache and take some pain relief medication, he symptoms will go away, but it doesn’t change the fact you are getting headaches because of insufficient sleep.

We can’t treat the symptoms of the homelessness response system and expect systemic change to take root. Channel your inner toddler and keep asking why, until you simply can’t answer that question anymore.

That’s where you will find the systemic challenge in the system, and can identify the intervention that you want to test and think will make a difference in your community.

It’s at this point that you can work with us at CAEH to draft the project aim. It’s important that this aim is a “SMART” objective, which stands for:

- Specific – the target population that you want to support must be clearly defined, whether that is people experiencing unsheltered homelessness, youth newly entering homelessness.

- Measurable – you must be able to determine based on your quality data if you are reaching your targeted outcome

- Achievable – the goal should be realistic. Introducing one small change is likely not going to end homelessness in your community, but what is the actual impact this change could have?

- Relevant – Is this goal important within the context of your community? If there is political will or collective prioritization within your community to address homelessness for a targeted population, you should work within that context.

- Time-bound – Grants through HRIF are one-time and for a maximum of 12 months. Don’t set an objective to be met by 2035, because this HRIF project will only last one year or less, so there should be a clear end date for your project.

A strong aim will look like this: “Our community will reduce chronic total homelessness by 18.3% by increasing the number of monthly move-ins by 5, for a total of 60 additional move-ins by the end of the project.”

It’s important to note that priority populations for HRIF applications are people experiencing unsheltered, chronic or veteran homelessness.

Good partnerships in the community are key

The project that is submitted should take your local context into account and advance local priorities in the community.

If your community is motivated to see a response to rising unsheltered homelessness, maybe your project is focused on encampments. If you’ve been talking about how to do a better job engaging with the local hospital, you might introduce a project that focused on the intersection between health and homelessness.

Take Prince Edward Island’s HRIF project as a good example.

Take Prince Edward Island’s HRIF project as a good example.

There were a lot of agencies working to support young people in the province, but there was a gap in prioritizing and connecting youth experiencing homelessness with housing.

So, the community entity developed a youth wrap-around housing project with the aim of reducing chronic youth homelessness by 48%.

Ultimately, your project proposal should fit within the web of work already happening and shouldn’t feel like yet another initiative to be run off the side of your desk.

It’s important to engage local partners throughout the entire project process, both in the design and the execution of the project.

The organizations that are eligible for HRIF funding are the community entities. So local agencies interested in operating an HRIF project should connect with the local community entity.

Similarly, if the project proposal is being initiated by the community entity, think about which agencies have specific expertise or mandates to support the target population.

In St. John’s, Newfoundland, the community entity End Homelessness St. John’s noted in their 2024 Point-in-Time count that 92% of people experiencing homelessness responded to the survey saying they were living with at least one disability.

In response, the community entity partnered with a local agency that already has experience helping to house people with disabilities to reach their target aim of reducing chronic homelessness by 10%, with a focus on people with disabilities.

Crucially, consider how to meaningfully partner with Indigenous-led organizations—something we’ll address in more depth in a future article with the National Indigenous Homelessness Council, a coalition of all Indigenous-led community entities and advisory boards across Canada.

Indigenous people are disproportionately over-represented among people experiencing homelessness right across Canada. Indigenous-led organizations are grounded in self-determination and Indigenous ways of knowing, and they already have the connections and expertise to address Indigenous homelessness.

Ultimately, strong partnerships will centre people experiencing homelessness, and the specific target populations you’re trying to support through this project.

A clear plan for data collection and analysis

Finally, having a clear plan for measuring the impact of your project is key to a strong HRIF application.

It means you need to be able to answer the questions:

- What data do we need to look at?

- Who can collect that data? Is someone already collecting it?

- Will we have access to the data?

- How often will we gather around that data and understand together if we need to pivot or change anything in our journey to reductions?

At the Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness, our Improvement Advisors and data team will help you define the data measures, analyse the real-time results of your project, and advise on any pivots you may need to make.

We want to support communities to develop strong projects with clear data and lessons that can be shared nationally to scale up our national efforts to end homelessness.

There are three different types of measures that we can support communities to identify:

- Outcome measures—this is identifying what we want to achieve. It’s the desired result. It’s reductions in homelessness, either through reduced inflow into homelessness, or accelerated exits from homelessness.

- Process measures—which focuses on answering the question of are we doing the things we said we were going to do? This could be the number of referrals made to the newly hired housing support workers, and the number of engagements those staff members are having with the target population of people experiencing homelessness.

- Balancing measures—which is about if the changes that you’ve made in one part of the system causing problems elsewhere. This could mean looking at move-ins for other populations that are not being targeted by the HRIF project.

Having this data is essential.

We’re collecting it so we can make data-driven decisions that will result in lasting change, that will help end homelessness for good.

We know this was a lot of information, but we promise that CAEH will be with you every step of the way through the application process and the implementation of your projects.

Reach out to your community Improvement Advisor or hrif@caeh.ca at any time with questions.

Apply now!

Calls for Expressions of Interest now open! Learn more information and submit your Expression of Interest by 4 PM ET on March 13, 2026.